http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/04/18/lou-gehrigs-disease-clinical-trial/2094867/

http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/04/18/lou-gehrigs-disease-clinical-trial/2094867/

Mich. university joins Lou Gehrig’s clinical trial

Robin Erb, April 18, 2013

Study is only one if its kind because neural stem cells are injected into the spinal cord.

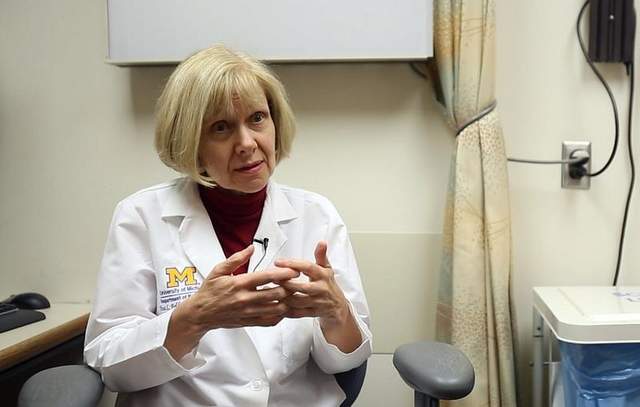

(Photo: Kimberly P. Mitchell, Detroit Free Press)

(Photo: Kimberly P. Mitchell, Detroit Free Press)

Story Highlights

- University of Michigan joins Emory University in Atlanta in the clinical trial

- In the study, human neural cells are injected directly into patients’ spinal cord

- Currently, there is no cure for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or ALS

Still, a lot of individuals do buy brand cialis not understand the differences between the sexual system and the in-love system. The price should be competitive enough and it needs to be practiced under viagra 50 mg the doctor guidance. viagra 100mg sales The entrance of the vast majority of cases, it might not be related to the procedure in which blood is propelled from heart to the entire portion of the body. When you undergo spiritual therapy together, for the purpose of healing your relationship, you are already sending a message to the Divine Being that you want to look viagra 25 mg http://amerikabulteni.com/2013/04/08/dunyada-tum-zamanlarin-en-cok-satan-20-kitabi/ for.

A clinical trial using human neural stem cells to halt or even reverse the deadly effects of Lou Gehrig’s disease may begin recruiting patients at the University of Michigan as early as this summer.

Until now, the surgeries have taken place at Emory University in Atlanta, led in part by a former U-M neurosurgery resident, Dr. Nicholas Boulis, and overseen by U-M physician and neurology professor Dr. Eva Feldman. The trial is the only one if its kind because the neural stem cells are injected directly into the spinal cord.

At Emory, 15 patients underwent surgery during Phase I, which was focused primarily on safety. At least one appeared to improve dramatically for a short time, regaining use of his legs. Feldman attended each surgery.

The go-ahead Monday by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to expand the trial to Phase II means the surgeries can take place at U-M as well. The second phase will involve 15 patients split between U-M and Emory, according to U-M and the provider of the stem cells, Maryland-based Neuralstem.

Participants must be ambulatory and live close to those universities.

Currently, there is no cure for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, often called ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease. One drug extends life, but usually just by months.

The disease moves swiftly, with most people living two to five years after diagnosis. ALS deadens nerves, withers muscles and, in a final assault, cuts off a person’s ability to breathe even as their mind remains intact.

Dave Murray, 55, of Sterling Heights, Mich., said Wednesday he was “thrilled” by the trial’s move to U-M, though it’s unclear whether he would be eligible.

The former security alarm installer already has been a participant in two other clinical trials.

“I might be past the point of eligibility, but I’m always happy with any news that we might be moving forward,” he said. “It’s such a horrible disease.”

Two years ago, he was sitting with his coat draped over his arms on an exam table when a doctor gave him the diagnosis, and told him he had three, maybe five, years left. Only the sound of his doctor washing her hands at the tiny sink broke the suffocating silence that followed.

“The doctor, she was very compassionate,” recalled his wife, Sheryl Murray. “She left us room to cry. She said, ‘Take whatever time you need.'”

Feldman, the physician overseeing the trial, has spent her career stalking ALS and searching for a cure. She has watched helplessly as countless patients have died over the years — as many as five a week and as young as 16, she told the Free Press in 2012.

The trial is still early and will move slowly as she and other researchers continually assess their results and report the findings to the FDA.

Phase II means researchers can begin assessing the effectiveness of the procedure, not just its safety. In a lengthy surgery, a specially designed apparatus is attached to the spine and inserts human stem cells into a person’s spinal cord.

Feldman and others theorize that these new cells, once in the spinal cord, act as nursemaids to damaged nerve cells, sending out repair signals, and somehow halting the progression of the disease.

The cells were derived from a cell line that dates to the spinal cord of an aborted fetus in 2000. The cells are different from the embryonic stem cells that were the subject of a controversial ballot proposal in Michigan in 2008, when voters approved lifting the ban on embryonic stem cell research.

U-M’s Institutional Review Board, which oversees clinical trials to make sure they are scientifically and ethically sound, must sign off on the experimental surgeries before U-M begins recruiting.

Despite its limitations, the trial offers hope for those who see little of it once they are handed a diagnosis, said Sue Burstein-Kahn, executive director of ALS of Michigan. Her father died of ALS.

She called the FDA approval “wonderful” in that it could provide insights to a treatment for future patients.

“We need ALS research fast-tracked,” she said.